"But wanting to justify himself,

he said to Jesus: And who is my neighbor?"

Luke 10:25-37

The Catholic church follows a liturgical cycle of readings. What this means is that the readings at each mass are pre-determined, scheduled, following a 3-year plan. The cycle completes itself and starts over every 3 years. Years are designated A, B & C---and currently, we are in year C. What this means in practice is that instead of a priest or liturgist selecting particular passages from scripture because they fit some pastoral concern or address a specific issue, the readings are determined by the cycle and every 3 years on the 15th Sunday of Ordinary Time, we hear the same series of readings including the story of the Good Samaritan. One of the odd blessings about such a system, is that the choice is not ours, the message is not selected by us, but imposed upon us and that imposition, if we allow it, can become a blessing of opportunity. It calls us out of the hamster-wheel of our habits and hungers and preferences, and invites us to look at life through a different lens, see the world around us from a different point of view.

And so, in the midst of all the strange and terrible goings on in our country, a president who seems to think he is a king, a congress that acts like cartoon minions, and agents of the government running around in masks arresting nursing mothers, day-laborers, and college students, we might have wanted to hear a message about justice or about the collapse of society, about God’s wrath on corrupt leaders… But, instead this Sunday at mass we will hear the parable of the Good Samaritan, and each of us will be given the opportunity to consider: what kind of neighbor am I?

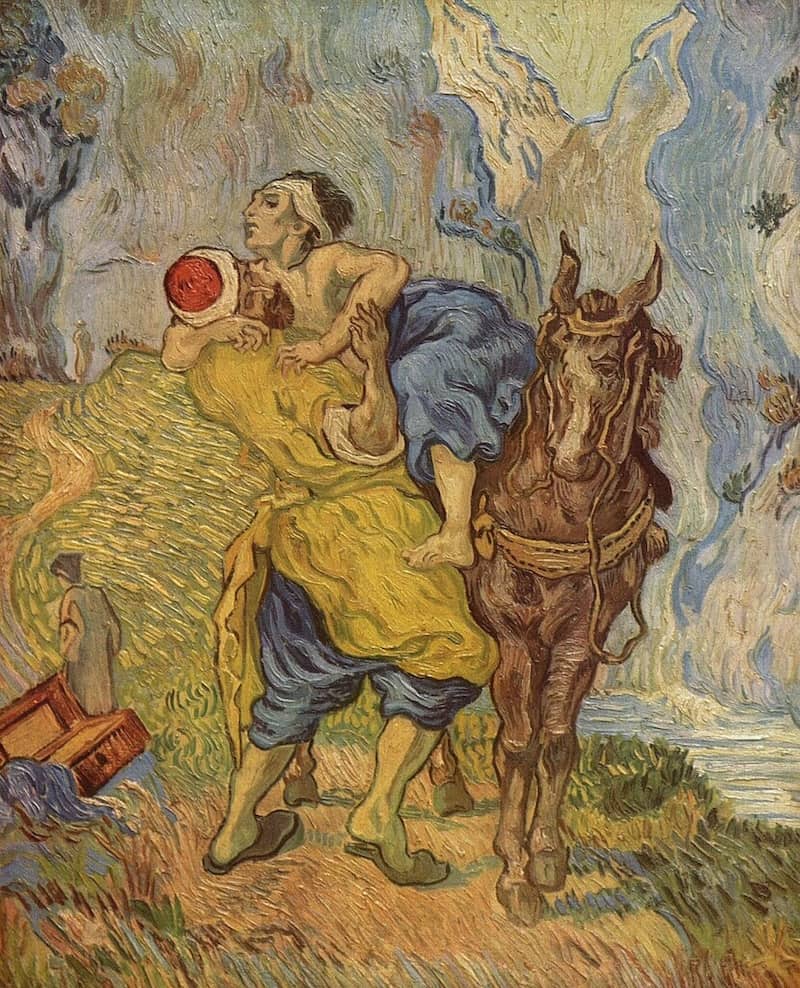

The story of the good Samaritan is probably one of the most familiar of all the parables. It is the story of a man who is beaten and robbed and left for dead on a roadside and three people who walk by his naked body. Two of them, a priest and a lawyer, keep going. They see the man, but walk on without helping. Only the third, a Samaritan (someone Jesus’s audience wouldn’t have wanted to associate with), stops and helps the man, caring for his wounds and taking him to safety. Re-reading this parable I have come to wonder if it may be the most radical of all the parables. Not only does the Samaritan stop and help the wounded man, but he takes him to an inn, watches over him, then pays the inn-keeper extra money to help.

And it all starts with a lawyer asking about the law, about the rules, asking about what is required to be a good Jew; as if he is trying to get Jesus to say: these are the minimum requirements to avoid breaking the law, to stay out of trouble with God. The lawyer has quoted the law to Jesus, the rules: You must love God with all your heart, and love your neighbor as yourself. And when Jesus affirms it, the lawyer, as if looking for a loophole, asks: But, who is my neighbor?

The lawyer’s simple question reverberates with the self-justifying sound of fear. Behind it one senses a fear of obligations and limitations, and the very human worry about having enough, about running out of time, energy, resources. But instead, Jesus answers with a story of generosity and compassion, discomfort and self-sacrifice. The Samaritan is on a trip, headed somewhere, he doesn’t know the man, has no obligations toward him, and yet he alone, of the three responds with love; he alone sets his own plans and needs, perhaps his own obligations and limitations aside responds with compassion, selflessly allowing the needs of another to become an opportunity to serve. Historically, Samaritans were seen by the Jews as outcasts or rejects; heretics and half-breeds. And yet it is the Samaritan, not the “good Jews,” the Priest and the Levite, who shows concern for the victim, who treats even a stranger with compassion, with love.

Instead of answering in legal terms, Jesus flips the question with a story about radical kindness. Shifting the focus from requirements and culpability to generosity, He asks the lawyer: Which of the three, do you think, acted like a neighbor? He turns the focus away from othering, from borders and tribal distinctions --who is my neighbor—making it personal –what kind of neighbor am I?

Who is my neighbor, the lawyer asks, and Jesus responds with a parable about a stranger, and radical compassion.

Jesus is challenging us to act with love not just toward family and friends, classmates or co-workers, not just the easy and the familiar, but to treat with love, with radical generosity, even when its uncomfortable, when its unplanned and disruptive to our schedule, even when it’s scary. He calls us to see through the Law into the Love. A Love that connects, that binds us all, friend and foe, family and stranger.

And there are few stranger than our current president, and few more frightening, and possibly none who needs love more –unless, of course, we count the widows, the orphans, the homeless, the refugees, the prisoner, the naked, the hungry, the thirsting…

And yet, even as I write this, I wonder might we not find all these qualities lurking somewhere beneath the prideful and belligerent façade of this man who seems to think he is a king. And yet, again, are we not called to love all people? Not just those who are easy to love, who make us feel comfortable, or safe. The real opportunity comes unplanned, in the uncomfortable, in the chance to give of ourselves completely, without expecting anything in return.

And one thing this parable makes uncomfortably clear: it is impossible to love someone if we are too busy “othering” them. Whether it is the immigrant, the refugee, the disabled, the different, or just a poor victim left wounded and naked in a ditch.

One of the blessings of having a liturgical cycle, is that readings are forced upon us; imposed, instead of proposed. And because they are, they can catch us off-guard, unprepared, surprising us with their prophetic truth and demanding that we pay attention. In a sense, they come as unexpected as an encounter with a stranger in need. Whether it’s comfortable or not, we are called to listen, to engage, and if we are willing—to respond, to be changed, to let the words challenge and change us.

Perhaps this moment in American history is a similar kind of challenge. We can debate the president’s policies and behavior all we want, but we must realize—he is ours, we elected him, and in some very frightful way—he is us! He is a challenge to be met, and we can either keep walking, pretending we don’t see, or we can stop and say: this cannot be. I must do something.

Is this not a time when we musts stop looking at borders and races, memberships and “tribes,” and instead open our eyes to the humanity of all people, look upon even those who don’t look like us, act like us, think like us, not as a problem to be avoided or cast out, but as an opportunity to encounter and become. Instead of asking: Who is my neighbor? we must ask: Who is in need? And what can I do to help? In this unexpected and unplanned moment, we find not just a challenge or a duty or an obligation, but an opportunity to become the people we all want to be, the person who walks toward the cross, the neighbor who—in our hour of need—we all hope to see.